There’s punishment without crime for some noncitizens facing immigration troubles, advocates say.

By Gabriela ReardonNatalia Puriy’s appearance at an immigration court in Florida in January 2006 began like many that she and her husband, James Turner, had attended previously. The judge once again admonished the government attorney to obtain the necessary paperwork so he could rule on Puriy’s petition for political asylum, and then adjourned the hearing for another six months.

But after the hearing, as the couple entered the building’s elevator, two immigration agents followed. Turner recalls that one agent shoved him aside and asked his wife if she was Natalia. When she said she was, he proceeded to detain the 48-year-old Ukrainian immigrant without explanation. That wasn’t what Puriy, a teacher, was expecting when she applied for America’s protection following a wave of killings in her native Ukraine that targeted outspoken anti-communist teachers, leading her to fear for her life.

“I asked him who he was and what he was doing, and he said they were retaining all people coming in. When I demanded his name, he slammed his badge in my face and told me to shut up and get out of his way,” Turner, a U.S. citizen, said in a recent interview.

Three hours later, Turner learned the government was placing his wife in the Intensive Supervision Appearance Program (ISAP). Run by a division of the Department of Homeland Security, ISAP began in 2004 as an alternative to detention for immigrants who could otherwise be detained for alleged immigration violations. But that day, Puriy felt the force of a program that some lawyers and advocates claim has instead become an alternative form of detention – too often ensnaring people who shouldn’t be detained at all. They say ISAP is overly restrictive and doesn’t effect the cost savings it was designed to – while some 610 New York residents, and 3,973 immigrants nationwide, are currently enrolled. Though it’s a relatively small number, this group of people appears to be caught in the gears of a gray area of government policy – one where either being outspoken, or not outspoken enough, could be the wrong move for someone whose immigration status is precarious.

For those already detained for immigration offenses – such as entering the country without permission or overstaying a visa – the way ISAP works is to grant release on the condition that participants agree to a set of strict rules, including a 12-hour curfew, three face-to-face meetings per week with a case worker, and unannounced telephone calls and home visits from the authorities. Each immigrant is also fitted with a GPS (Global Positioning System) monitoring ankle bracelet and must install voice recognition technology on his home telephone line, which allows caseworkers to confirm they are speaking to the ISAP participant during routine phone calls. After 30 days in this intense phase, participants usually graduate to the intermediate phase, in which the bracelet is removed and the visits and phone calls reduced. The final stage involves fewer visits and phone calls, and usually continues until the immigrant is deported or cleared of charges. Only those not subject to mandatory detention, and not deemed a threat to the community or a flight risk, can participate in ISAP.

Puriy, who married Turner in 2002 and relocated from upper Manhattan to Del Rey, Florida, spent not 30 but 80 days in the intense phase of the program. “They told us because we were being mouthy and making trouble that she would have to remain in the program longer,” Turner said from their current home in Florida. (Puriy was unavailable for an interview.)

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the agency within the Department of Homeland Security that polices immigration, says the aim of ISAP is to free detention bed space in facilities to make room for some of the average 214 immigrants ICE arrests every day, and to ensure the people it releases appear in immigration court. The government launched the program in 2004 in eight U.S. cities and reports that as of last month, 8,500 immigrants have participated since its inception. In New York City, where the program became available in November, a total of 749 immigrants have participated.

ICE outsources ISAP to Colorado-based Behavioral Interventions, Inc., a private firm with experience managing home-arrest and felon reintegration programs across the country. The company also manufactures the GPS-monitoring ankle bracelets and radio frequency receivers used for such programs. According to the federal watchdog group OMB Watch, which tracks government spending, since 2004 ICE has paid Behavioral Interventions nearly $40 million to provide monitoring services in Baltimore, Philadelphia, Miami, St. Paul, Denver, Kansas City, San Francisco, Portland, and more recently Orlando, Los Angeles and New York City.

According to ICE, the agency has deported about one-third of ISAP participants, including those who opted for voluntary departure after proceedings had begun.

But lawyers and immigrant advocates say that like Natalia Puriy, many of the immigrants entering ISAP are not detainees who are released into the program. Instead, they say, ICE is offering the program to people who have already been released on bond by an immigration judge or who have never been detained. Most accept the so-called volunteer program because they are told their only alternative is to enter detention.

While ICE says it does not track participants’ detention status prior to entering the program, anecdotal evidence provided by attorneys and policy analysts suggests it is more likely that people who have already been released from detention will be placed in the program.

“We are regularly hearing that it is rare for someone to be released into ISAP. More and more clients are going into immigration courts, fully complying with the conditions of their release, and then going into ISAP. The irony is that a person has proven him or herself and is then given more restrictions,” said Annie Sovcik, staff attorney for the Baltimore-based Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service.

Kerry Bretz, a Manhattan attorney experienced in deportation defense who has several clients in the program, agrees.

“This is meant to keep a short leash on people who are at the end of their case, who are looking to leave the country soon on an order of deportation, or who are ordered removed but have no travel documents, so that when it comes time to execute the removal order, [ICE] has the person nearby,” Bretz said.

Although some advocates criticize the harsh conditions and restrictiveness of the program, many say that for those who are detained in a facility, ISAP is preferable. The problem is few people in detention are offered the ISAP program. “I don’t see anyone who is detained suddenly benefiting from ISAP,” says Bretz.

ICE Public Information Officer Richard Rocha did not respond to City Limits’ multiple requests for input on the operations of the program, including assertions that some immigrants are wrongfully being subjected to an “alternative form of detention.”

Efforts like ISAP find support in groups such as the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), a Washington, D.C.-based group that advocates stricter immigration controls. “There has to be some way of holding on to people once they’re apprehended,” says spokesman Ira Mehlman. “There is a need to have people under detention or a close form of supervision. There’s definitely an inadequate number of detention beds available. Obviously Congress needs to appropriate more funds so that we can hold the people we have spent the money to go out and find.”

“Even if you are considered a lesser flight risk, it doesn’t mean there’s no risk at all,” Mehlman said. “We have supported detention because there’s an extremely high rate of people absconding.”

The government modeled ISAP after the Appearance Assistance Program (AAP) piloted between 1997 and 2000 in New York City as a collaboration between the Manhattan-based Vera Institute of Justice, which studies the justice system, and the Immigration and Naturalization Service (which has been renamed and folded into Homeland Security).

INS hired the Vera Institute to test whether community supervision could improve court appearance rates and thus decrease its reliance on detention. Like ISAP, the program required regular in-person meetings, telephone calls and home visits. But, unlike ISAP, the program did not use electronic monitoring devices, and it also provided participants with referrals to human services like food pantries, health clinics and English classes. Both programs refer immigrants to free or low-cost lawyers. The result of the pilot was a 91 percent appearance rate for participants, in contrast to a 71 percent appearance rate for non-participants.

ISAP has been even more successful, according to ICE. Since the program’s inception, 99 percent of participants nationwide appeared for their removal hearings, and 95 percent appeared for final order hearings, at which the court issues its decision. In New York City, the overall rate of appearance has been 97 percent, although final order appearances rest at 67 percent.

Some lawyers and advocates are troubled by ICE’s use of electronic monitoring devices in the form of ankle bracelets placed on participants during the intense phase. The American Bar Association’s Commission on Immigration calls electronic monitoring overly restrictive, saying it “constitutes another form of detention, rather than a meaningful alternative” to it.

Janis Rosheuvel, an organizer with New York City’s Families for Freedom, a group fighting family separation resulting from deportation, sees ISAP as another example of the federal government criminalizing immigration and the deportation process. Being undocumented, Rosheuvel says, is a civil violation, not a criminal one, and the process is not meant to be punitive.

The program “is not an alternative to detention. It is an alternative to people’s freedom of movement. The notion of alternatives to detention is that people will be released into the community … not placed in non-stop monitoring,” she said.

The question of whether the government’s use of GPS monitoring devices constitutes detention, or is just a condition of release, became central in the case of an immigrant challenging the “arbitrary and unfair conditions” of her detention. In a ruling published in May, Los Angeles Immigration Judge Lori R. Bass wrote, “The use of ankle bracelet monitor does cause the loss of a great deal of Respondent’s liberty, and requires confinement in a specific space.”

Oren Root, director of Vera’s Center on Immigration and Justice, headed the pilot program in the late 1990s and said his team considered using electronic monitoring at the time, but ended up opting against it. “We decided to try to see whether a combination of supervision and incentives, such as referrals to the community, could be used without using electronic monitoring. We were successful in showing we could get good results without using [it],” Root said.

In addition to attaining high court appearance rates, the government argues that ISAP presents a cost-saving alternative to the ever-growing demand for detention beds, which has continued to climb since changes to immigration law in 1996 broadened the category of deportable immigrants – but has really peaked since the Bush administration launched Operation Endgame. That effort, launched in 2003, aims to deport all undocumented immigrants and those with criminal convictions by 2012. In 2008 ICE spent nearly $1.7 billion on immigrant custody; the number of detention beds reserved for immigrant detainees is rising from 20,000 in 2006 to a projected 33,000 for 2009. Bed space in a facility currently costs the government $95 daily per detainee, while ISAP costs as little as $12, according to the American Immigration Lawyers Association.

But because ICE is not applying the program to people already detained and emptying detention beds, critics say, the intended cost-savings effect is lost. “The way [ICE] sees the program, it is more expensive. They are viewing it as an add-on, to be applied to people who are already out,” instead of using it on people currently occupying a detention bed, says Kerry Sherlock Talbot, the associate director of Advocacy, Family and Due Process for the American Immigration Lawyers Association.

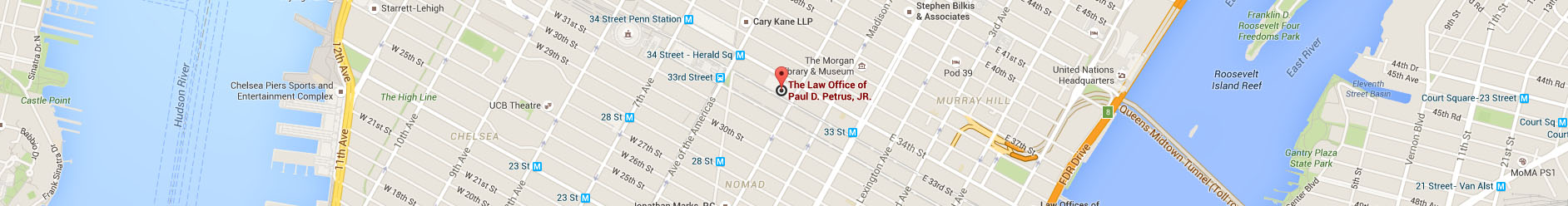

Paul D. Petrus, Jr., a criminal defense and immigration attorney in Manhattan who has one client in ISAP, says the program may actually lead to further overcrowding of detention centers if immigrants either fail to comply with the requirements, or decline to participate – which can result in ICE sending them to a facility.

Much of the concern over ISAP revolves around the lack of transparency in how the government runs the program. It has not shared, for example, its enrollment criteria or the specific indicators of success that permit participants to graduate to the less intense phases. Individual officers appear to have a lot of discretion in each case and decisions on individual cases sometimes appear arbitrary.

For this reason Petrus declined to identify his client, describing him only as a Chinese national who lives in Queens and who entered the United States illegally as a child. An immigration judge ordered him deported more than a decade ago, but because China does not recognize his citizenship, he remains in the U.S. For years he has been checking in regularly with immigration officials – but like Natalia Puriy, he was recently given an ultimatum: either enter ISAP or be detained.

“Our dilemma is, if he speaks up he risks being detained [in a facility] but if he remains silent he surrenders his constitutional rights and remains in house arrest,” Petrus said.

He describes this policy as arbitrary and capricious – exactly how Turner and Puriy felt the agents behaved toward them on their court date nearly three years ago. Petrus says thus far he has seen no criteria or been given any documentation explaining why his client is in ISAP.

“Only the gods and the federal government know when this will change,” he said.

– Gabriela Reardon